“Dragons are all about attitude and personality, but the way that you have to convey that is wonderfully sardonic…see, they can be any way that they want to, so what kind of id—which is what they’re the symbols for in Western culture—is going to pass up the opportunity to really go for bad?”

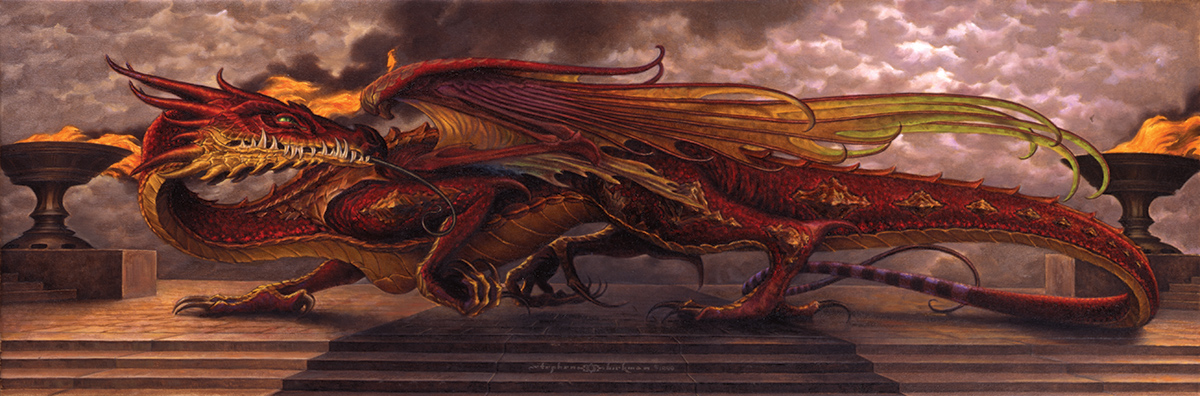

When it comes to dragons with attitude, the denizens of Stephen Hickman’s sketchbooks have no equals—sinuous, seductive, and, often, just plain sinister.

“Dragons are the ultimate design element. They have a type of archetypal impact, which C. G. Young defines as a “universal, energy releasing iconic symbol,” so you’ve got the kind of psychic-releasing power of the image to begin with. But then it can be anything you want, because no one’s ever seen one so there’s nobody around telling you it’s not realistic if you make it look plausible. The challenge is that you have to make it look circumstantial and plausible, but at the same time you can turn them around and put them in all of these fantastic designs and shapes, so they’re the ultimate power design shape.

“The way to be really convincing about that is to go back to nature and the infinite, incredibly beautiful forms of nature—that stuff is all the more effective, I think, when you mix the elegance of natural forms with it anyway. So, you get that sort of dichotomy, the ambivalence between the repellent and the beautifully attractive.”

“Art Nouveau, for instance, was all about going back to nature for rhythms, instead of using classical geometry with all of these straight lines running all over the place. Alphonse Mucha was a huge influence on my work—he understood nature from the inside out, and understood how we instinctively respond to the endless phi ratios found in nature—like the spirals of a sunflower seed or the inside of a seashell— because we’re probably all put together on the same basis from an atomic level up.”

Hickman’s consideration of the dragon also extends beyond the aesthetic and into the mythic archetype.

“The definition of archetype is something that appears in the psyche, in the mythos of a civilization. And it seems from studies of world mythology that the dragon, in some form or another, appears in every single one of them. So, it’s one of the most powerful archetypes, possibly a genetic memory—if you believe in that sort of thing—of dinosaurs and so forth or just a deep-seeded, hard-wired reaction to things that are reptilian. Since the dragon appears in every mythology the world over this makes them one of the most powerful iconic images—for whatever you choose to make them the symbol of, it works.

“For example, let’s look at the mid-late 1970s, when the dragon really seemed to explode in popularity. Why did that occur? Well, I could explain this according to the definition of myth as expounded by Joseph Campbell in that a mythology is a mechanism that the human psyche uses to relate to an infinite and chaotic universe. As the pace of human civilization quickens and the pace of change quickens, the need to re-mythologize and reconstruct that mechanism becomes more important and has to be redone at a quicker rate.”

“Also, the emphasis through the 80s of the “me” generation—the yuppie quarterly mentality—means that the id needs its symbology. You see rampant greed going on and there’s the dragon. What’s the dragon do? He piles up a bunch of junk a sits on it. He can’t do anything with it.

“It’s like politicians—the guy that dies with the most digits in an off-shore bank account wins. What can he do with it? Nothing. There’s only so much money you can spend. So, you have the perfect symbol. If artists are the sort of intuitive harbingers of the collective psyche, there you have it.”

For Hickman, the fluid nature of the dragon archetype means that there’s no ‘one size fits all’ approach to creating one.

“Once you cover all the rest of it, it’s back to the emotions. Consider the dramatic range of possibilities, starting from Glaurung the Dragon, this enormous gold, really sinister, malevolently intelligent dragon in the Silmarillion, with the dragon spells and the ability to cause everlasting trouble just by speaking, let alone by being his imposing self. Then you can go to more whimsical levels of sardonic attitude—I don’t care for dragons that are silly and I don’t care for dragons that are cute, that’s going over the deep end, over to the other spectrum—but within that range you can go for the impersonal chaos of nature, in other words having less of a personification of a personality involved in a dragon.

“You have to just go with the drawing and see what turns out. If I was doing something like St. George, which is the impersonal embodiment of nature—man against nature, man against chaos, or good against evil—you go for the impersonal and classical treatment, which plays down the emotional aspect. But there was one that I did for a project where you have Rapunzel with her hair being used as dental floss by this character of a dragon and that’s a good example of a more human characterization.”

Regardless of the emotional treatment of the subject, Hickman’s dragons begin with the drawing.

“I tend to orchestrate things, I don’t do real painterly concepts. I think the success of a dragon, for me, is how much time I’m willing to spend on the draftsmanship—which is a considerable amount of time. If I approach a serious picture that has a potential, I will refine the drawing and I think this is a critical thing. The study of nature and the feeling you have for it, as well as the conviction that you can do it, of course, but then the time that you are willing to devote to refining the image and working out your color schemes and making it work up is conducive for me to do dragons. I think that’s why my dragons are popular. It’s just because it’s something I really get a charge out of doing and I’m willing to take the time to do it.

“And that’s not an unimportant thing. If you really enjoy what you’re doing, that’s going to communicate itself virtually every time, particularly to people who are not trained as artists because they respond intuitively and instantaneously to genuineness and they react against attitudes of, “Oh, I know what these people want, I’ll give them a dragon.” That kind of pretension is something that people react to negatively immediately, whether they can articulate it or not.

“Your life experience builds up to a certain intensity of vision—you have to draw on that to have anything to say. Use your dragon as a carrier wave, but it’s the intensity of feeling or what your reaction is to the experiences you’ve been through that is what your vision is that you’re expressing.”

Fans of fantastic art have been fortunate enough to experience the intensity of Stephen Hickman’s visions as they’ve wound, flapped, raged and flaunted their ids across our collective vision through four different decades, reflecting back from that deep wellspring inside all of us.

“On Dragons”

By Stephen Hickman

Originally published in The Art of the Dragon (2012)