“An artist once said ‘a painter should be of his own time.’ I am clearly not and proud not to have been.”

Richard Bober doesnʼt mince words when it comes to his assessment of 20th century art.

“The only thing more repugnant than 20th century painting is 20th century music. The paintings of Matisse and the music of Schoenberg; thereʼs a vision of hell that would frighten even Dante! Evelyn Waugh described the last century well as having ʻ. . . ripped up the nourishing taproot of tradition and let wither all the dearest things of the world.ʼ”

Given this perspective, itʼs no surprise that Richard draws his artistic inspiration from previous centuries: Hals, Vermeer, Ingres, and especially J.M.W. Turner. Needless to say, this predilection for pre-Modernist painters didnʼt do him any favors as a student at the Pratt Institute in the early 1960ʼs. A self-described “die-hard reactionary forced to study under a series of tenth-rate DeKoonings and Jackson Pollack clones,” Richard was never a part of the ʻinʼ crowd at Pratt.

“He was part of a little group that used to hang out together,” recalls Barry Klugerman, a fellow illustrator and long-time friend. “We werenʼt part of any clique that was there. There were a group of fair-haired boys that the professors loved, but Richard was always too eccentric for that, even though everyone was in awe of his talent.”

Instead of cleaving to the establishmentʼs idea of “art,” Richard devoted his time at Pratt to focusing on the works that he loved. “Ingres was a passion of his. He would do etchings of Ingresʼ famous Monsieur Bertin with tremendous detail – even more than you could see in the original, like reflections in the eyes. They were just incredible. He would work for hours and hours on copper plate on an area about 2 inches square. When he pulled the proofs, you could not see any sign of a human hand – everything consisted of nearly microscopic lines,” Klugerman remembers. “He would also copy Ingresʼ pencil drawings over and over again, but with tighter detail and even more luminescence than the originals, using tiny hatchings that would read as tone.”

Richard would never graduate from Pratt, being, as he put it, “booted out in 1966, after flunking gym, and holding the school record for cutting classes.” Fortunately for him, his career as an illustrator was already under way, having begun in 1959 in a rather unique manner.

“I met a beautiful woman who looked like a young Ava Gardner. As an illustrator at her agency I was paid, but I would have worked for nothing. Rent a film called Bhowani Junction and look at Gardner in that white sari and youʼll see why . . . .”

Klugerman remembers the work. “Richard showed me those early advertising pieces – pictures of a man locked into blocks, 3D cubes that were cut through to show pieces of an ear, or a face. They were extremely sophisticated, even at that age.”

Although Richardʼs work at the agency was short-lived, the association lived on for years as the young Gardner look-alike appeared in painting after painting, providing the archetype for Richardʼs ideal female figure once he began his illustration career in earnest by the early 1970s. From that point until the turn of the century, he worked for nearly every major publisher, focusing first on mysteries before moving to predominantly science fiction and fantasy titles.

Working with a combination of acrylics and oils and utilizing complex glazing and texturing, Richard would often spend endless hours reworking paintings. His process consisting of doing an underpainting in umber and then glazing over it, so that the underpainting would be protected. Once that was done, he would try out an endless variety of flourishes and glazes, wiping them off with a cloth when he wasnʼt satisfied with the way they turned out, and trying again until he was happy with the end result.

If this sounds like a recipe for a never-ending painting process, itʼs painfully true in Richardʼs case. When asked what made his work different from that of other illustrators, Richard wryly summed up the situation: “My work usually arrives at the publisherʼs desk a year or two after the deadline expired.”

Klugerman expanded a bit on Richardʼs comment.

“Richard has never been able to meet deadlines or deliver things in a timely fashion. He was always doing things that never got finished. Itʼs not because he canʼt work swiftly – he really knows the terrain, and his facility with the brush is unmatched. But he always worked to satisfy himself, not to the constraints of a deadline. Da Vinciʼs famous quote could serve well as Richardʼs credo – ʻArt is never finished, only abandoned.ʼ”

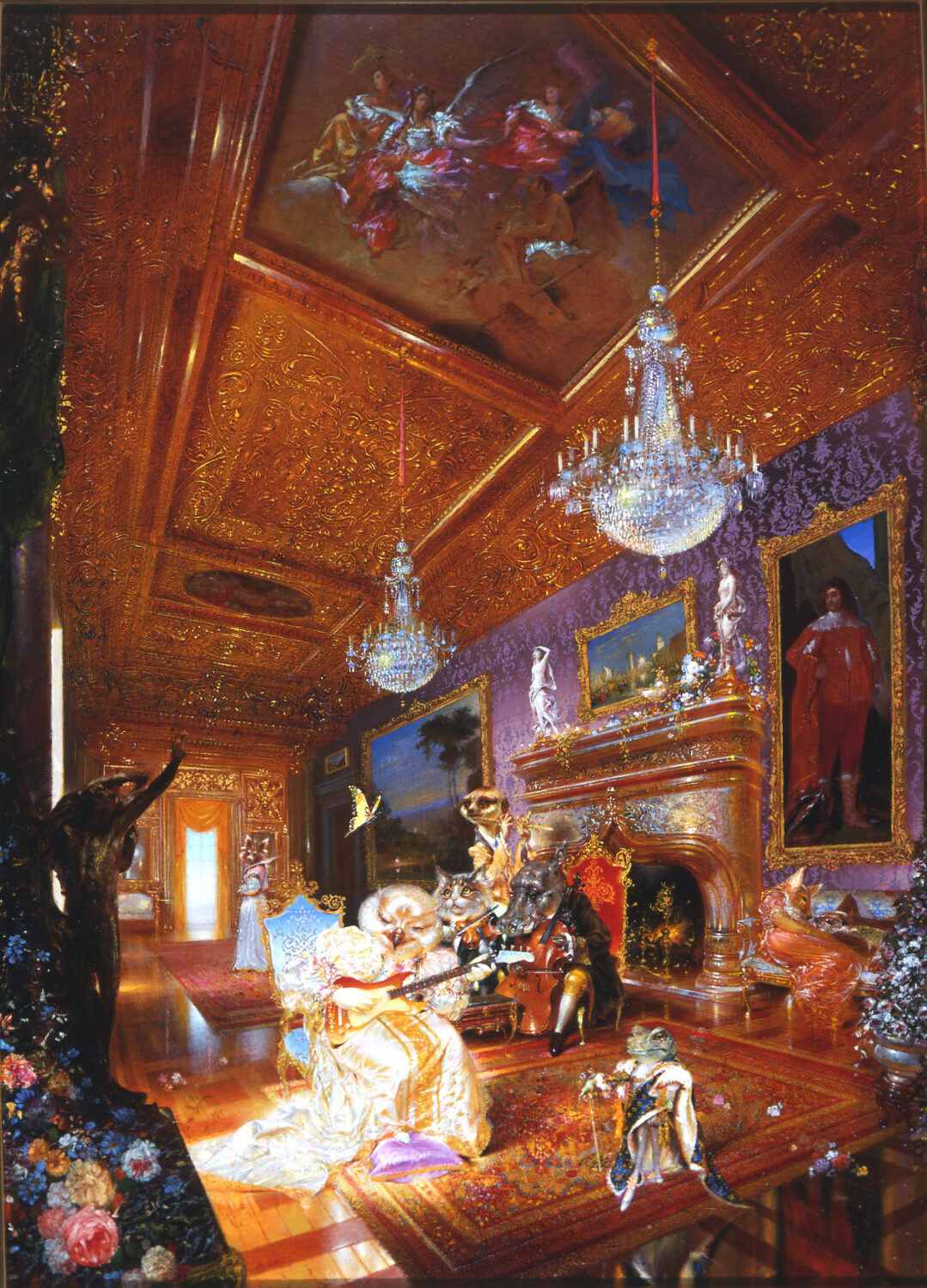

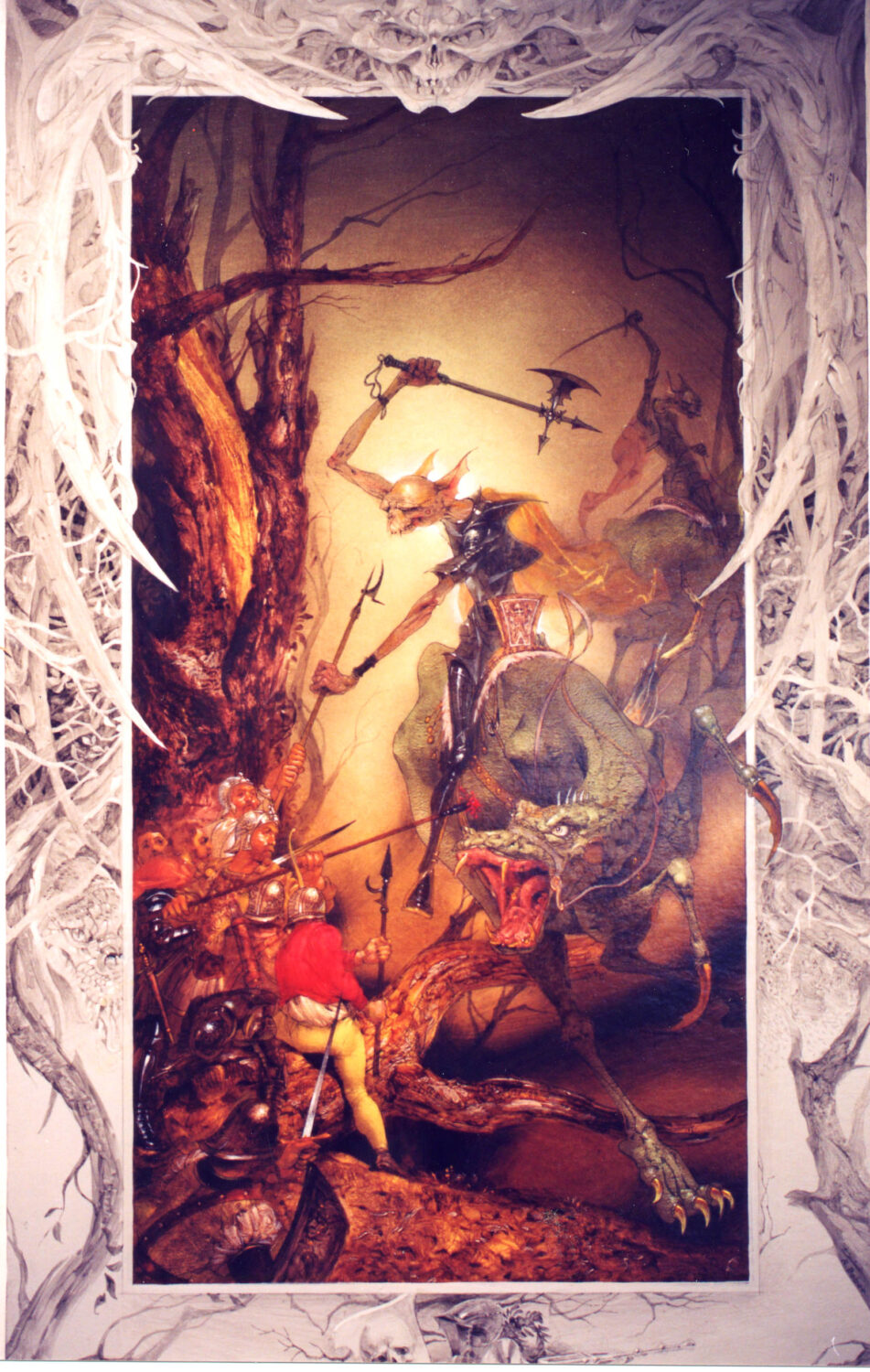

The end results, though, have been worth the wait. If art was judged purely on technique, Richard would inarguably be one of the greatest painters of the last century. His paintings seem to come with their own illumination sources, the glazing and texturing putting forth more light than they are receiving from the outside world, as if each brush stroke created a tiny faceted jewel within which light dances and scatters. While most illustrators are adept at manipulating light to create form and space, Richardʼs work extends far beyond that. Not only is he able to add texture to a piece to create shape and form, he is also able to utilize texturing that reads as light in a way no other artist in the genre, before or since, has been able to master.

Unfortunately, there is a price to be paid for this majestic technique. The manipulation of light, color, and texture that Richard uses requires all the facilities of the human eye to decode. The camera, a pale imitation of the eye at best, has no chance of capturing the paintings in more than an approximate way. The paintings are vibrant and powerful enough that a sense of his skill manages to make its way through the reproduction process, but only a sense.

“Itʼs one of his failings,” admits Klugerman. “He never worked for the process of reproduction – only for himself. The great orchestration of his painting – the color, the depth, the vibrancy – is lost in the reproduction process. The harmony of the painting is thrown off.”

This fact, combined with Richardʼs remarkably low output in the field, has led to an odd dichotomy in his status. Those who know Richardʼs work consider him to be among the finest painters to ever work in the genre, but to many, including a surprisingly large number of his peers, he is a relative unknown. Many of his finest works have appeared on the covers of relatively obscure books, and Richard has never shown any interest whatsoever in promoting himself or his work. “Ars ipsa loquator,” he might say – “the art speaks for itself.”

Richard is a purist at heart, and it is that purism that leads to his view of contemporary art, and his place within that arena. Or lack thereof.

“An artist – I believe it was Picasso – once said, ʻA painter should be of his own time.ʼ I am clearly not, and am proud not to have been.”

Klugerman agrees. “Heʼs really someone who has always considered himself apart from the century he was born in. He has a tremendous disdain for Modernism. Conceptually and technically, he has seen a lot of what he considers to be really shoddy work be accepted as ʻart.ʼ”

While this is true, itʼs equally true that no artist can literally relocate themselves into another century. Richard is absolutely a modern – small “m” – painter, but he is the continuation of the line of tradition that was broken by the Modernists. Heʼs not slavishly copying the Old Masters, but rather borrowing elements and mannerisms from their work and applying them through his own prism. One might see a Kalf lemon peel peeking out from a background, but the way the elements are stylized is unique, and Richardʼs paintings look identical to nothing else that has come before or since.

Certainly, in fantastic illustration, a harkening back to the Old Masters for inspiration is not unique to Richard. His uniqueness comes from his rare, transcendent ability for execution, and to translate the most mundane assignment into something more.

The great Spanish illustrator Jose Segrelles once said that the great challenge of illustration was to take the most pedestrian assignment and transcend it by transfusing it, somehow, into a true work of art. Richard has done that, going far beyond what is required by an assignment, creating wonderful tableauxs of paint and light that are in every way complete as a work of art.

However, since the turn of the century, Richard has simultaneously turned and been forced into more personal work. The advance of serious arthritis, which first struck in the 1980s, has further slowed his already glacial production pace, and the modern publishing environment has no room for production delays due to missed art deadlines.

Unfortunately, Richard has yet to make the move into the gallery market, where his low output might be as much a bonus as a shortcoming.

Klugerman explains. “The thing with Richard is that he never found an all-encompassing theme to concentrate on, like many gallery artists do. People in the arts like artists who can be pigeonholed – ʻThis is what we expect from Artist X.ʼ But, thematically, Richard has never developed a consistent voice. His great accomplishment is the wonderful way, visually, that he executes his work, and the richness of his artistic arsenal, not any particular conceptual ideas. If he had, early on, started gearing his work towards the gallery market, he would have consolidated a very strong following.”

For Richard, who has never really worked towards the needs of the client, but rather towards satisfying himself, perhaps the difference is academic. He continues to create the most beautiful paintings he can, and, after almost 50 years of painting, his career has now outlasted some of the movements he so disdains, bringing the gifts of the Old Masters into the 21st century.

Evelyn Waugh would be pleased.

“Gift of the Old Masters”

By Patrick Wilshire

Originally published in Visions of Never (2009)